All the normal matter in the Universe is made up of teeny tiny building blocks that are far too small to be seen with the naked eye.

But we humans aren’t about to let the physical limitations of our eyes stop us from looking at things we want to see, right?

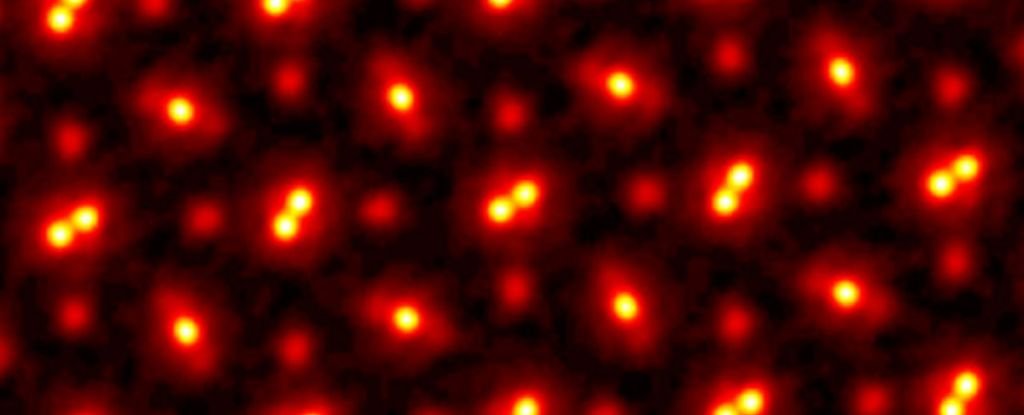

The image you see above was made back in 2021 by a team led by physicist Zhen Chen, formerly of Cornell University and now at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Those dots are the atoms in the crystal lattice of a piece of praseodymium orthoscandate (PrScO3), at a magnification of 100 million.

The only reason the image looks a little fuzzy around the edges is not because the resolution is poor, but because atoms don’t stop jiggling about, which results in a little thermal motion blur.

No matter how good technology gets, though, that record-breaking resolution is unlikely to ever be beaten. That’s because there’s a limit to how much resolution we can achieve on these atomic scales, and this is pretty much it.

“This doesn’t just set a new record,” said physicist David Muller of Cornell University, when his team’s results were published in Science.

“It’s reached a regime which is effectively going to be an ultimate limit for resolution. We basically can now figure out where the atoms are in a very easy way. This opens up a whole lot of new measurement possibilities of things we’ve wanted to do for a very long time.”

This achievement is the work of the pinnacle of atomic imaging technology, a technique called ptychography.

Ptychography isn’t actually a direct imaging technique, but a kind of interferometry. That’s the generation of an image from interference patterns. Electrons were fired at a sample of praseodymium orthoscandate; when these electrons hit the atoms in the material, they bounced off.

By measuring the bounce patterns, or scattering, of these electrons as the beam is moved around, the imaging system can generate an image of what the electrons are bouncing off.

Now, because praseodymium orthoscandate is a compound, what you see here are three different kinds of atoms. The pairs of bright blobs joined together are praseodymium. The single bright blobs are scandium. And the faint red blobs are oxygen. All these atoms are bound together to form the pure, perfect crystal imaged by Chen and his colleagues.

The breakthrough in atomic imaging has implications and applications for physics and engineering, granting us the magnificent ability to study atomic structures in high-resolution and three dimensions. We can use this for everything from materials science to quantum communications.

“We want to apply this to everything we do,” Muller said. “Until now, we’ve all been wearing really bad glasses. And now we actually have a really good pair. Why wouldn’t you want to take off the old glasses, put on the new ones, and use them all the time?”

The things humans can do when they really put their minds to it are just incredible.

You can find the team’s full paper in Science.