For some 37,000 years, the soft, furry body of a three-week-old saber-toothed ‘kitten’ lay cradled by Arctic permafrost, its head, limbs, paws, and torso remaining almost perfectly preserved by the cold.

In 2020, the juvenile’s body was recovered from its grave in the Russian republic of Yakutia and examined by a team of researchers whose excitement is palpable in their recently published report.

“Findings of frozen mummified remains of the Late Pleistocene mammals are very rare,” the researchers explain.

“For the first time in the history of paleontology, the appearance of an extinct mammal that has no analogues in the modern fauna has been studied.”

Remains of long-buried animals are often scattered by predators, scavengers, and the elements, meaning much of our understanding of extinct animals that predate human history is often based on a few bones from here, a few teeth from there.

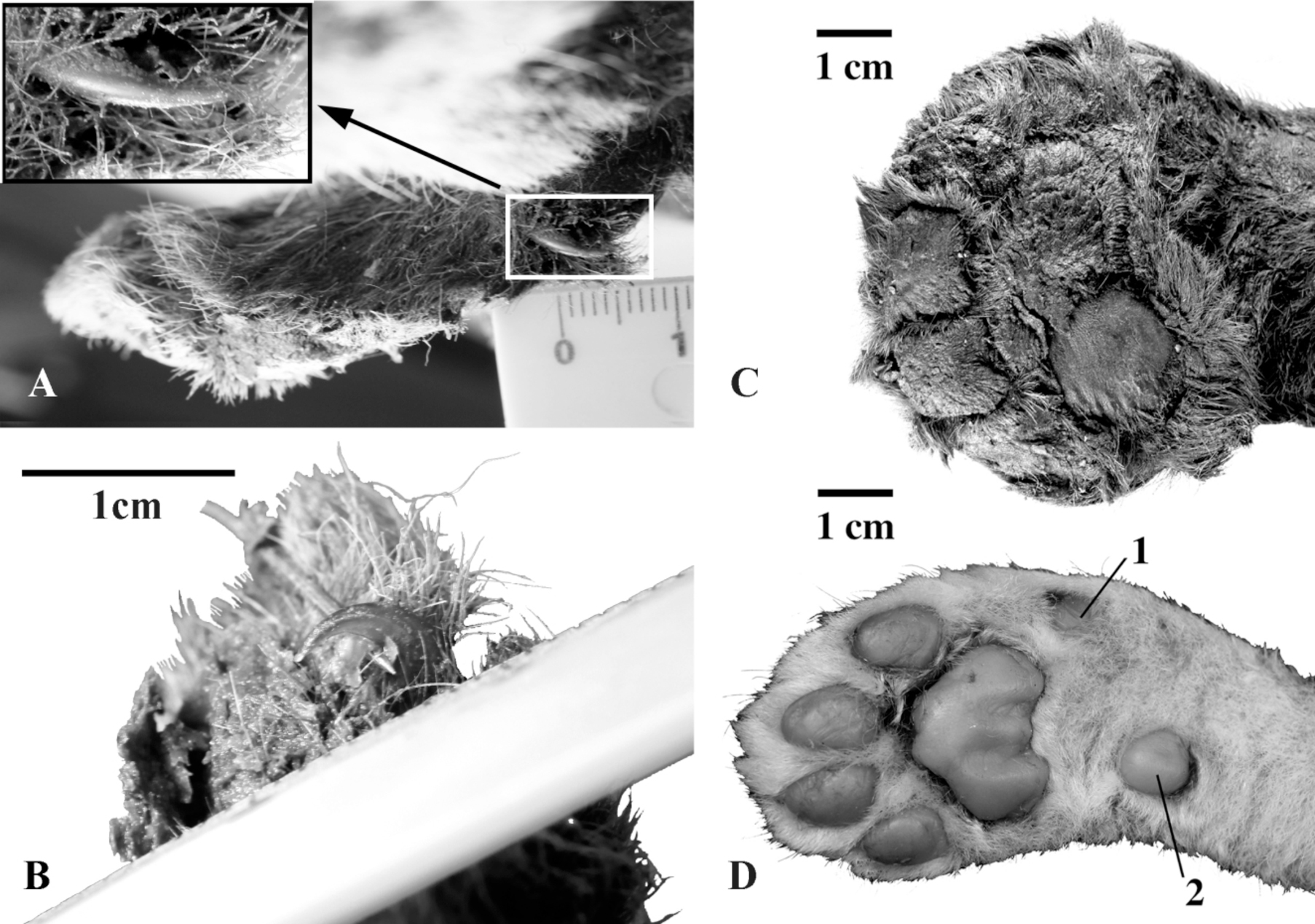

But this mummified saber-toothed cat (Homotherium latidens), whose Late Pleistocene life was cut short for unknown reasons, was found with its front half relatively intact, with incomplete pelvic bones, femur, and shin bones encased in ice nearby.

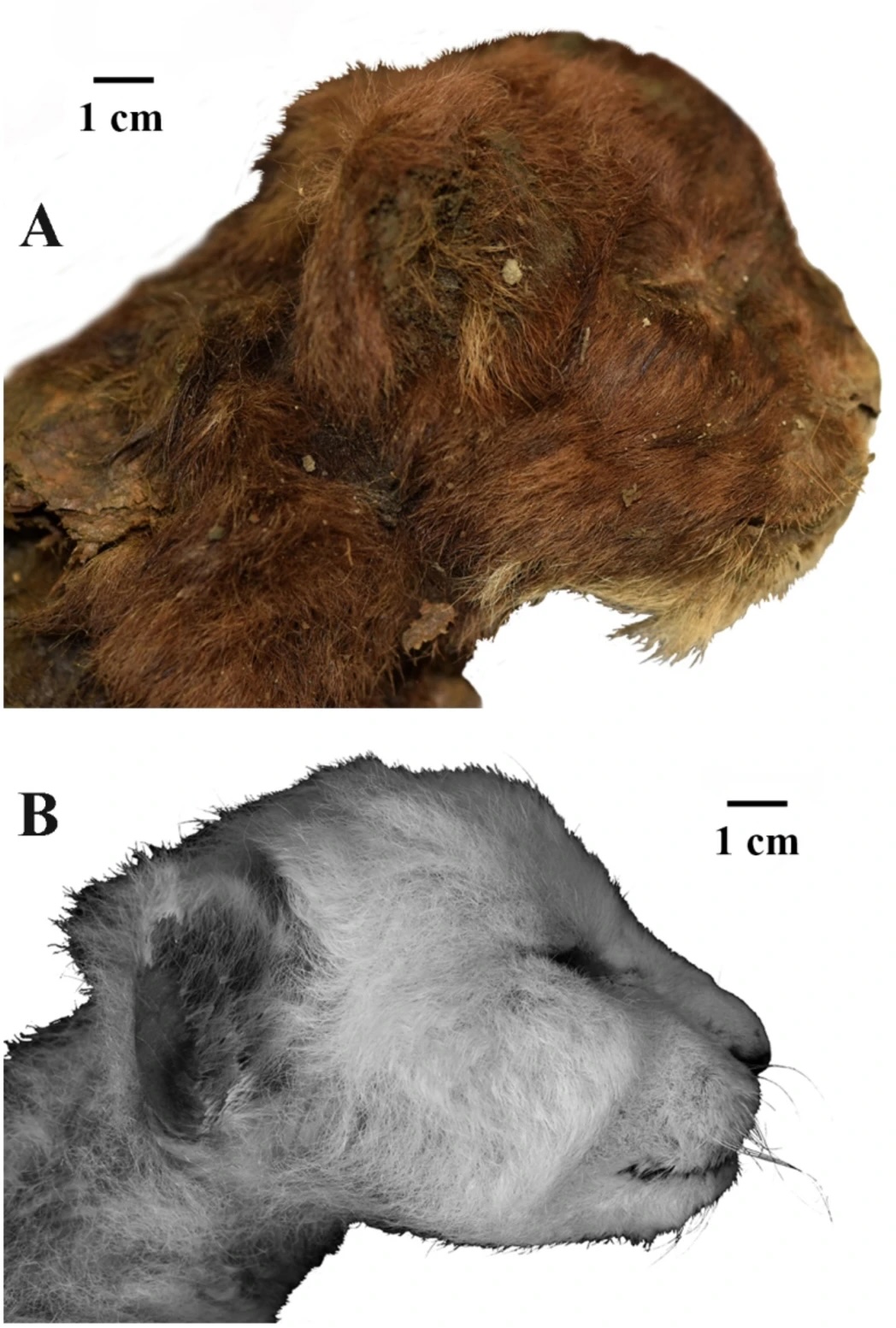

The astonishing discovery offers unprecedented insight into the species’ physical features, from its fur and the unusual shape of its muzzle, right down to its perfectly preserved toe beans – ahem – I mean, its front paw.

An analysis of the cat’s remains reveals key differences to modern lion cubs of a similar age, estimated to be around three weeks. By comparing this species to a living relative, we gain a better understanding of the long-gone species, which lived in a drastically different world than the one we know.

“The discovery of H. latidens mummy in Yakutia radically expands the understanding of distribution of the genus and confirms its presence in the Late Pleistocene of Asia,” the authors note. The mummy, found in what is now northeastern Siberia, is the first evidence that the species’ range extended so far north, so long ago.

The Late Pleistocene is known for massive changes to the Earth’s climate, including the Last Glacial Maximum, which peaked around 26,000 years ago. We can learn a lot about life during this period from the remains of preserved flora and fauna that lived and died in a rapidly changing climate.

Despite its premature end, the cub appears to have been well-adapted to the cold: its paws are relatively wide compared to those of its living relatives. It also has no carpal pads, the lack of which is thought to be an adaptation to low temperatures and walking in snow.

H. latidens is the only species in its genus known to inhabit Eurasia at this time, and specimens from northern Spain suggest it mainly hunted large prey, like aurochs and deer.

Compared to a three-week-old lion cub, the prehistoric baby cat’s muzzle has a noticeably large mouth, small ears, and a “very massive neck region”, along with elongated forelimbs.

Its dark brown fur is “short, thick, soft,” and longer on its back and neck than the fur on its legs, with beardy tufts on the corners of its mouth. And like any self-respecting feline, it even has whiskers: two rows on the upper lip.

“One of the striking features of the morphology of Homotherium, both in adults and in the studied cub, is the presence of an enlarged premaxillary bone,” the authors write.

This jaw shape allows for the genus’s characteristic row of large, cone-shaped incisors.

So far the authors have analyzed only the most striking and unusual physical features of this young cat, but they’re already working on another paper that will discuss the cub’s anatomy in more detail.

This study was published in Scientific Reports.