1UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, London, UK

2Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, UK

- Correspondence to: H Bedford h.bedford{at}ucl.ac.uk

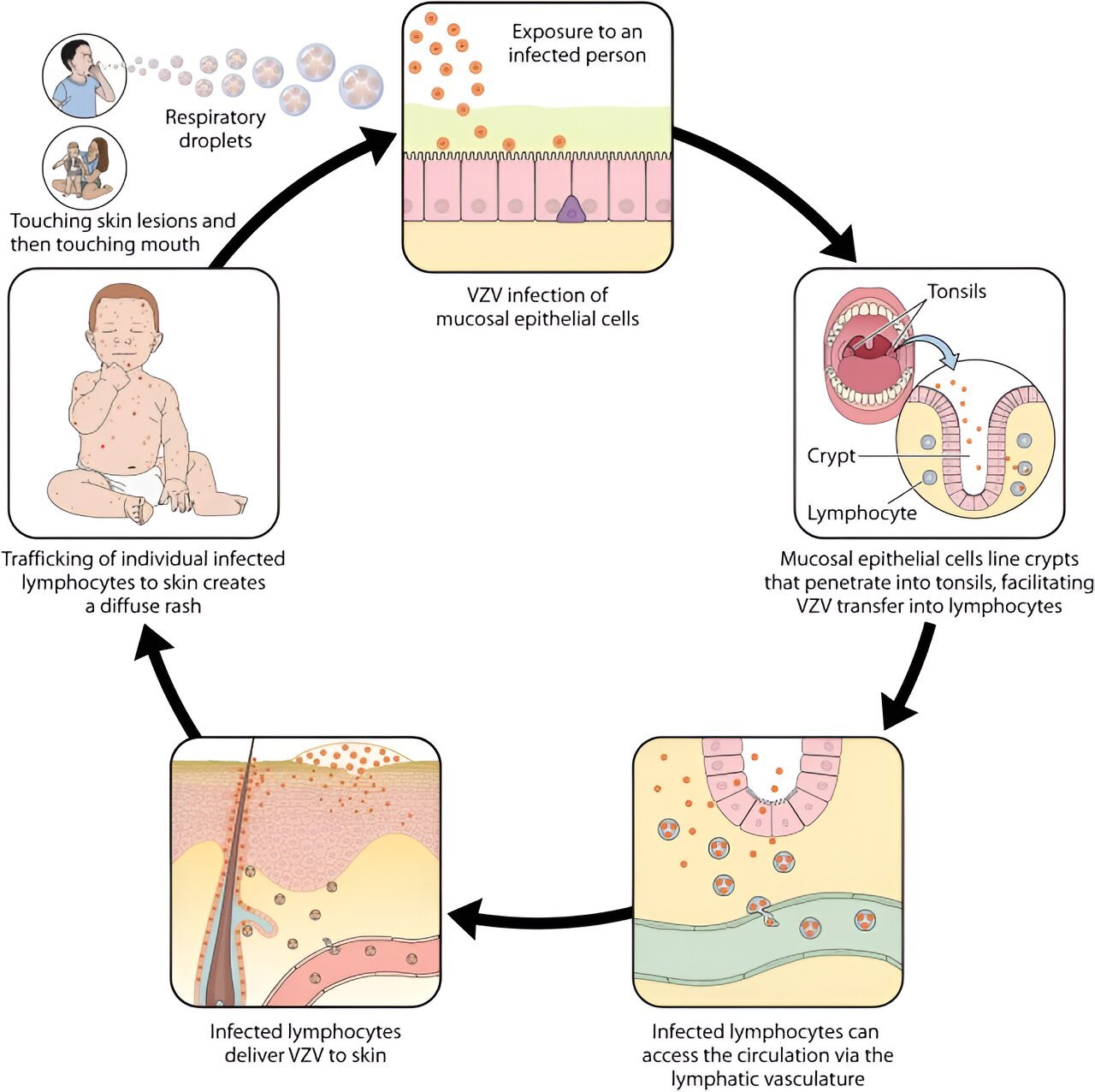

On 19 January 2024 a national incident was announced in England because of a rapidly growing outbreak of measles centred on the West Midlands.1 Such outbreaks were predicted by the UK Health Security Agency last summer, particularly in London.2 In April 2023, when cases were rising in Europe, Jose Hagan of the World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Europe, warned that “All countries, including those verified as having eliminated endemic transmission of measles, must be vigilant for possible importation and spread of this highly contagious disease.”3 Globally, comparing 2022 with 2021, cases of measles rose by 18% and deaths by 43%.4 In 2023, over 42 200 cases were reported across 41 EU states by the end of November, with five deaths.56

In 2014 and 2015, the UK reported fewer than 100 cases of measles a year, the lowest ever recorded, and WHO declared that the UK had eliminated measles. This does not necessarily mean no cases, rather that there was robust evidence that endemic transmission had been interrupted.7 This status was lost in 2018 but regained in 2021 because the covid pandemic was associated with large reductions in measles, along with many other infections.

Infants in the UK have been offered safe and effective measles vaccination since 1968—first with a single antigen vaccine and, since 1988, through the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine—so why have we reached this situation? Uptake of MMR at age 24 months in England rose to over 90% in the mid-1990s but fell to 80% in 2003-04 after publication of a now discredited paper suggesting a link with autism. Uptake recovered to 92.7% by 2013-14 but subsequently fell gradually each year to 89.3% for the first dose in 2022-23 and 84.5% for the second dose at five years.8 No local authority in England now achieves the 95% uptake of the two doses needed for population immunity,8 and there are stark differences in uptake by geography and between cultural and religious groups. The combination of low uptake in the 2000s, leaving many young adults susceptible to measles now, and more recent suboptimal uptake in children, has resulted in an accumulation of unprotected individuals, often in pockets, enabling outbreaks.

Reasons for low uptake

The multiple factors affecting vaccine uptake include a poor understanding of disease severity because of lack of experience. The case fatality in sub-Saharan Africa and some parts of Asia is about 5%, and even higher in refugees.9 Even in high income countries, measles carries a significant risk of death (1 in 1000-5000 cases). An adult died of measles encephalitis in the UK in 2019,10 but few are aware of this risk, which may explain why younger adults are less likely than older adults to consider vaccination important for children.11

Pressures on primary care undermine vaccine programmes, with parents reporting a lack of reminders and difficulties making or attending appointments.12 Parents repeatedly express a need for easier access to trusted health professionals to discuss vaccines. This need has risen since the covid-19 pandemic, which influenced people’s views about vaccines in both directions—either underlining their importance or generating further questions or mistrust.12 Shortages of staff, including health visitors and practice nurses, have been substantial,13 leaving an important gap in access to these trusted sources of immunisation information.1415

Declining vaccine uptake is often attributed to vaccine hesitancy or even anti-vaccine sentiment. Misinformation is unlikely to change the minds of parents determined to vaccinate their children but may influence parents with doubts, concerns, or questions, particularly in the absence of advice from a trusted health professional. A clear distinction should be made between having questions and concerns about vaccination, which is to be encouraged, and being “anti-vaccine.”

Organisations such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Unicef, and WHO set out the strategies needed to achieve and sustain successful vaccination programmes.161718 They broadly include improving access, availability of trusted sources of information including local community leaders and health professionals, and ensuring that systems are in place to gather good quality data to monitor uptake and enable issue of recall and reminders.

Additional efforts are needed to ensure that children and young people who missed their vaccines during the pandemic are identified by checking their vaccine status at all healthcare contacts and in educational settings and vaccinating opportunistically as appropriate. Although the UK’s core vaccine offer should be centred on general practice, vaccine services must be tailored to different communities’ needs. This includes attention to the timing and location of vaccination clinics, and to the content of information, which should be available in multiple languages and formats.19 The message that it is never too late to be vaccinated should be communicated clearly.

Reversing the decline in vaccine uptake and preventing further disease outbreaks requires immediate action by healthcare providers and commissioners, with strong commitment and funding to implement these measures. Plans are already underway to bring the second dose of measles vaccine forward to 18 months20 and to implement a new vaccine strategy in England in 2025.21 Perhaps both should be implemented sooner.