Open up any novel by David Peace and you will find ghosts, and people beset by ghosts. The haunted are almost always from the north of England, except for the ones in post-World War II Tokyo. They are obsessive and prone to paranoia, as the haunted tend to be; their self-destructive streaks are galvanic and inescapable. The worse things get—things always get worse—the hauntings become propulsive, dissociative experiences. It’s fitting that the late Mark Fisher, high priest of Hauntology, was a big fan. “You are not living with the dead. You are living with the living,” Philip Roth wrote in Sabbath’s Theater. Peace’s characters aren’t afforded such merciful clarity. As one of the many disordered minds in 1977 muses repeatedly:

“This is why people die.

This is why.”

This is why people.

Peace doesn’t like to sit still. His books can be broken down into four groups: the Red Riding Quintet, an unforgiving neo-noir centering around The Yorkshire Ripper, a real-life serial killer who murdered at least 13 women and girls in the North of England during the 1970s; the Japan trilogy, about despair and corruption in Tokyo in the aftermath of World War II, books so laden with unresolved grief as to border on the supernatural; the football books, which are The Damned United, about the 44 disastrous days Brian Clough spent managing Leeds United, and Red or Dead, which recounts Bill Shankly’s socialist run as Liverpool manager; and GB84, a thriller about the 1984 National Union of Mineworkers strike (a thriller about a strike, that’s correct).

His restlessness makes for a lively game of contrasts but also hammers home that his legions of the haunted aren’t always confronting human ghosts. In addition to the human dead in the Red Riding books, the nominal protagonists must also face blighted, divested industrial cities, places like Leeds, Bradford, and Huddersfield, as well as morally vacant police and rapacious journalists. In GB84 and Red or Dead, it’s the looming spirit of strangled social democratic England—palpable, nearly visible, irretrievably lost. In Occupied City, the postwar military occupation of Japan is as much possession as military action. The victims of a mass killing at a Tokyo bank in 1948 serve as a chorus to the investigation of their deaths: “Between the Occupied City and the Dead City, here we dwell, between the Perplexed City and the Posthumous City.” Everyone in all these books is in some sense in between; the dead, for their part, aren’t going anywhere.

Peace’s newest book, Munichs, belongs to the football group. It very much is not an escape from ghosts. Like all of Peace’s books, it is born out of fact. In February 1958, Manchester United were flying back to England after a European Cup match at Red Star Belgrade. Their plane stopped to refuel in Munich, where a steady snow was falling. The pilots aborted takeoff twice, and on the third try, the plane hit a layer of slush at the end of the runway and smashed through a fence. Part of the plane was sheared off and hit a nearby house. The remainder collided with a fuel truck. Of the 44 passengers, 23 died; eight of those were United players. Those who walked—or crawled or hobbled or were dragged—away from the wreckage of the British European Airways Airspeed Ambassador suffered injuries ranging from mild to grave.

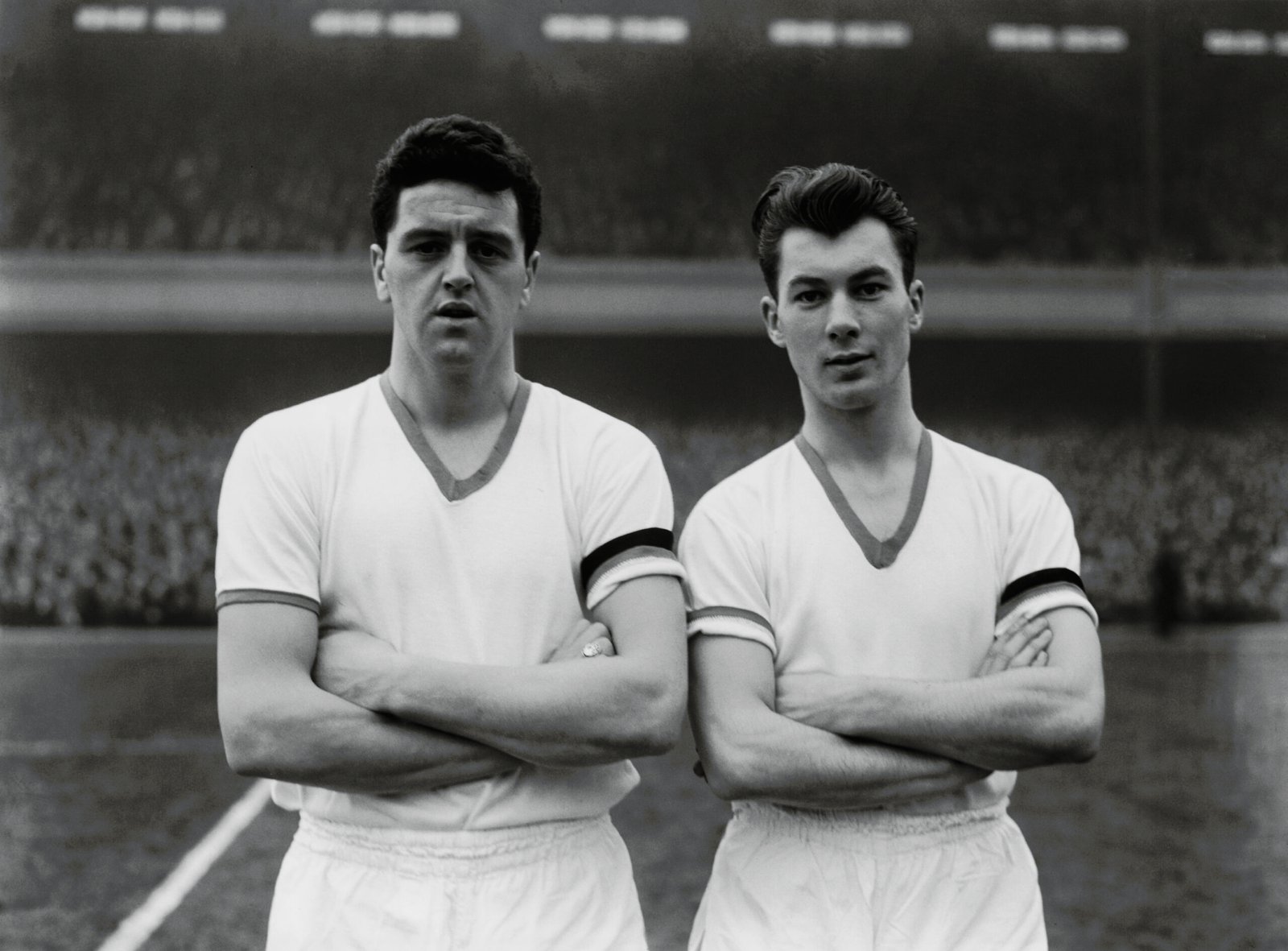

United were First Division champions two years running, and in second place at the time of the crash. They had the England international captain Roger Byrne and prolific scorer Tommy Taylor and the gracefully bruising midfielder Duncan Edwards. All three died, though Edwards passed 15 days after his teammates did. Their manager Matt Busby spent months in a Munich hospital, and left it in a deep depression.

Thirteen days after the crash, United beat Sheffield Wednesday 2-0 in an FA Cup match. The United team was made up of reserves, youth players, transfers, and two survivors: goalie Harry Gregg and fullback Bill Foulkes. Gregg and Foulkes, as the least seriously injured in the crash, serve as guides of sorts through the book’s opening section. The uncanny ordinariness that catastrophe imposes on people comes roaring through them.“The poor girl just stood there,” observes Gregg in the immediate aftermath, “barefoot in the snow, staring down, down at the ground, the abysmal ground.” (It is a genuinely grim coincidence that United’s opponent would be the club that, three decades later, took its own place in the registry of football tragedy through the Hillsborough disaster of 1989.)

Between the crash, the separation of the living from The Dead (as Peace stylizes them), the uncertainty at home in Manchester, a devotion to geography that extends to the names of tiny streets in little Northern towns, Munichs almost feels more like a book about an industrial accident, a mine collapse or a factory fire, than one about an international sports disaster. “[T]he hearse set off slowly, slowly made its way onto Sunningdale Road, then slowly left up Chassen Road, between the big, bare trees, slowly turning at the pub onto Church Road…” It helps to keep in mind how much smaller the sport was, then: the men who play the game lace up their boots each morning and go to their cold damp field to ply their trade, much like but not quite like their fellow laborers. When they come home it is not to circa-now EPL opulence but to parents, wives, landladies, babies.

Then as now, the gig was not a lifelong stint; the difference, then, was that it didn’t promise anything like lifelong wealth. The impermanence of a football career wasn’t a source of regret or looming despair but an inherent and normal part of the work. Like serving in the military, men knew that eventually they would at some point be cashiered, at which time they would need to find something new to pay the rent. Roger Byrne was training to be a physiotherapist after retiring. Tom Finney, who was one of the best forwards ever to play for England and has a cameo in Munichs, was also a plumber. Toward the end of the book, Jimmy Murphy, the assistant manager who took over the team following the crash, fumes about English wealth: “No wonder they needed all their fabled manners and codes of conduct, otherwise they’d slit each other’s throats.” Arthur Scargill and the National Union of Mineworkers would no doubt approve.

The survivor’s guilt running through the book is so unrelenting that Munichs can read like a séance for the living. “My biggest mistake was staying alive,” the plane’s surviving pilot says. Worse than not having the plane de-iced. Worse than trying to take off one more time. The worst thing the living can do is live.

Or so it would seem. The Dead are erratic creditors. The staff blame themselves for taking players to Belgrade they knew would not play. Those who sat at the front of the plane blame themselves for not sitting in the back, where most of the fatalities occurred. Those who continue to play blame themselves for taking places on the field that they should not have. Setting grief aside for just a second, surviving is very confusing. In The Drowned and the Saved, Primo Levi describes a gnawing supposition of survivors that they have betrayed The Dead. There is no logic to this belief, no substance behind it. Only a cloudy suggestion to further muddy the inexplicable.

After that mildly miraculous win in Sheffield, United won only one more league game that season. It is in the book’s third section, as the season stumbles to its end, that Peace picks up some of his trademark kinetic momentum. (The second section is essentially a procession of funerals; it is in every sense a dirge.) The team still managed to make the FA Cup final against Bolton and that damaged team, held together by obstinance and grief and the blind uncertainty of not knowing what to do without The Dead, just keeps playing.

This is embodied most fully by Bobby Charlton. Charlton is one of the best football players ever, full stop, no team or national qualifiers needed. He nearly gave up the game after the crash. The anguish and ambivalence he experienced, combined with sport’s habit of auto-mythologizing, create so many shadow iterations of What Went On With Bobby Charlton that Peace is, briefly, driven completely out of the narrative: “There are at least three versions of how things went when Bobby got back home to Ashington, the house on Beatrice Street.” This is not authorial license, just an accounting of what’s been put out there.

Charlton moves through the book, from crash to pitch, in a stupor, stunned at living, baffled by it, saddened at having to do it but doing it all the same. “He seemed ten times the player he was before the crash,” Peace writes, during the run-up to the FA Cup final, “which made no sense, but it was as though the talents of every lad who’d died had filled his boots, his legs, his brain, his heart and soul.” There is a strain of strange triumphalism throughout Munichs, sometimes uncomfortable for being mawkish, sometimes for its echoes of the crass instrumentalization of modern sports when they butt up against tragedy. (It’s a ghoulish hypothetical I’m not going to take up, but if something similar were to happen today, Roger Goodell, CAA, Nike, and MillerCoors would put on a memorial spectacle that would make Wagner’s Ring Cycle look like a TikTok reel.) Jimmy Murphy has a handful of monologues that boil down to Must go on, We must rise, and the like. United must play on. Life must continue. But it is not just that.

Beneath it is another, less sentimental notion: life will go on, and does not care if you go on with it. If Samuel Beckett’s “I can’t go on, I’ll go on,” the often badly misused closing words of The Unnamable, come to mind, here, it’s worth considering what comes before it in a typically massive, jagged sentence: “[Y]ou talk of murmurs, distant cries, as long as you can talk, you talk of them before and you talk of them after, more lies, it will be the silence, the one that doesn’t last, spent listening, spent waiting…” This is an industrial existence, a machine life, granted on brutal terms by mechanisms that aren’t even aware of the people on the other end of the transaction, let alone concerned with their wellbeing. You can choose to go on or not, but the world will still go on regardless. The cries will just grow more distant, more ghostly.

It is true that Munichs is Peace’s most conventional work to date, but that is only saying so much. What it really means is that at no point does the novel collapse into hypnotic incoherence or psychosis; not everything “succumbs to total murk,” in Fisher’s words. (By now it seems de rigeur to mention that, back in 2003, Peace was one of Granta’s Best Young English Novelists, in a class that included Zadie Smith and Rachel Cusk. So, consider it mentioned.) Fisher described Peace’s books as “brutal and unrelenting fictions that possess an apocalyptic lyricism.” Take this passage from 1980:

“I bend down and run my hand over the dark sides, over the heavy water, across the scratchings and the markings, the messages, the signs and symbols –

In my hand, black and bloody water –

I turn the torch upon my own hands, looking:

DEATH –

Never let her slip –”

That is fairly standard stuff in the Red Riding and Japan books. The writing is dense and baroque but also creates a rhythmic momentum that’s suffused with dread. Or consider the rhythms running through Red or Dead: “On the train, the train back to Liverpool…” “In the dugout, on the bench…” “In the house, in their front room…” In their repetition and consistency, this creates a rhythm that is grounding, guiding, even gently lulling, across 700 pages.

But Munichs is also Peace’s most humane work. The title, the plural city, may sound odd to those unfamiliar with the word. It’s an insult that opposing fans point at Manchester United. The moral darkness of that sentiment is made more clear by this typical terrace chant: Who’s that dying on the runway? Who’s that dying in the snow? It’s Matt Busby and his boys making all the fucking noise ‘cause they couldn’t get the aeroplane to go. It’s a memetic jeer; United, their players, their supporters: all of them Munichs.

In his author’s note, Peace says that his intention is to redefine the word as a point of pride for United. He is asking the reader to look back at the history itself, instead of at its weaponized iteration. It’s an admirable aim, but not an easy mark to hit; that the story is true and told with such diligent and delicate reverence likely does not outweigh the impulses of fanatics and assholes. Never mind that inhumane taunts are lingua franca among certain soccer fans, and that the past always slips into abstraction. The effort of living is enough of a strain, and doing so while also embracing grief makes for an oceanic burden. If anyone would understand that we’re all already doing all that we can to get through the day—to finish the match, to live in the world, to go on—one hopes it would be The Dead.