The availability of safe, effective COVID vaccines less than a year into the pandemic marked a high point in the 300-year history of vaccination, seemingly heralding an age of protection against infectious diseases.

Now, after backlash against public health interventions culminated in President-elect Donald Trump’s nominating Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the country’s best-known anti-vaccine activist, as its top health official, infectious disease and public health experts and vaccine advocates say a confluence of factors could cause renewed, deadly epidemics of measles, whooping cough, and meningitis, or even polio.

“The litany of things that will start to topple is profound,” said James Hodge, a public health law expert at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. “We’re going to experience a seminal change in vaccine law and policy.”

“He’ll make America sick again,” said Lawrence Gostin, a professor of public health law at Georgetown University.

State legislators who question vaccine safety are poised to introduce bills to weaken school-entry vaccine requirements or do away with them altogether, said Northe Saunders, who tracks vaccine-related legislation for the SAFE Communities Coalition, a group supporting pro-vaccine legislation and lawmakers.

Even states that keep existing requirements will be vulnerable to decisions made by a Republican-controlled Congress as well as by Kennedy and former House member Dave Weldon, should they be confirmed to lead the Department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, respectively.

Both men—Kennedy as an activist, Weldon as a medical doctor and congressman from 1995 to 2009— have endorsed debunked theories blaming vaccines for autism and other chronic diseases. (Weldon has been featured in anti-vaccine films in the years since he left Congress.) Both have accused the CDC of covering up evidence this was so, despite dozens of reputable scientific studies to the contrary.

Kennedy’s staff did not respond to requests for comment. Karoline Leavitt, the Trump campaign’s national press secretary, did not respond to requests for comment or interviews with Kennedy or Weldon.

Kennedy recently told NPR that “we’re not going to take vaccines away from anybody.”

It’s unclear how far the administration would go to discourage vaccination, but if levels drop enough, vaccine-preventable illnesses and deaths might soar.

“It is a fantasy to think we can lower vaccination rates and herd immunity in the U.S. and not suffer recurrence of these diseases,” said Gregory Poland, co-director of the Atria Academy of Science & Medicine. “One in 3,000 kids who gets measles is going to die. There’s no treatment for it. They are going to die.”

During a November 2019 measles epidemic that killed 80 children in Samoa, Kennedy wrote to the country’s prime minister falsely claiming that the measles vaccine was probably causing the deaths. Scott Gottlieb, who was Trump’s first FDA commissioner, said on CNBC on Nov. 29 that Kennedy “will cost lives in this country” if he undercuts vaccination.

Kennedy’s nomination validates and enshrines public mistrust of government health programs, said Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The notion that he’d even be considered for that position makes people think he knows what he’s talking about,” Offit said. “He appeals to lessened trust, the idea that “There are things you don’t see, data they don’t present, that I’m going to find out, so you can really make an informed decision.'”

Targets of anti-vaccine groups

Hodge has compiled a list of 20 actions the administration could take to weaken national vaccination programs, from spreading misinformation to delaying FDA vaccine approvals to dropping Department of Justice support for vaccine laws challenged by groups like Children’s Health Defense, which Kennedy founded and led before campaigning for president.

Kennedy could also cripple the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which Congress created in 1986 to take care of children believed harmed by vaccines—while partially protecting vaccine makers from lawsuits.

Before the law passed, the threat of lawsuits had shrunk the number of companies making vaccines in the United States—from 26 in 1967 to 17 in 1980—and the remaining pertussis vaccine producers were threatening to stop making it. The vaccine injury program “played an integral role in keeping manufacturers in the business,” Poland said.

Kennedy could abolish the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, whose recommendation for using a vaccine determines whether the government pays for it through the 30-year-old Vaccines for Children program, which makes free immunizations available to more than half the children in the United States.

Alternatively, Kennedy could stack the committee with allies who oppose new vaccines, and could, in theory at least, withdraw recommendations for vaccines like the 53-year-old measles-mumps-rubella shot, a favorite target of the anti-vaccine movement.

Meanwhile, infectious disease threats are on the rise or on the horizon. Instead of preparing, as a typical incoming administration might, Kennedy has threatened to shake up the federal health agencies. Once in office, he’ll “give infectious disease a break” to focus on chronic ailments, he said at a Children’s Health Defense conference last month in Georgia.

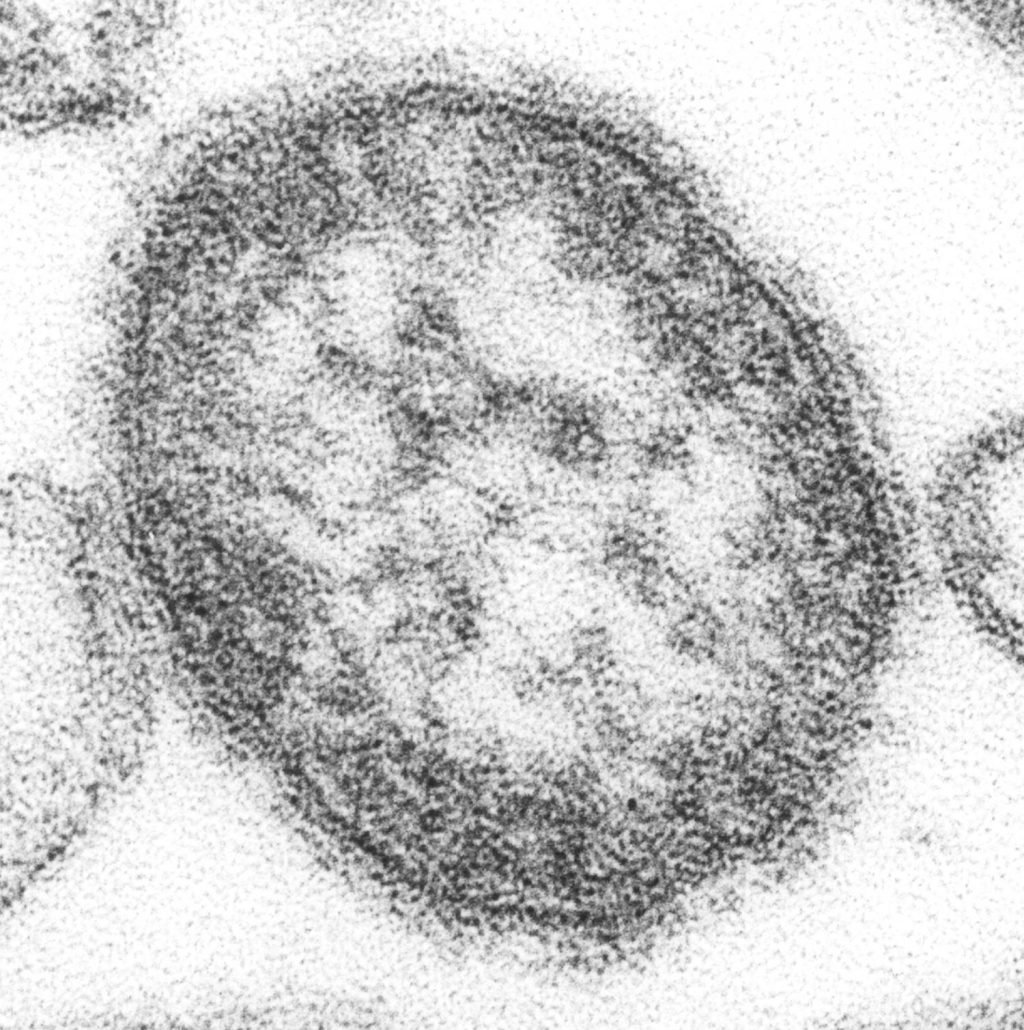

The H5N1 virus, or bird flu, that has spread through cattle herds and infected at least 55 people could erupt in a new pandemic, and other threats like mosquito-borne dengue fever are rising in the U.S.

Traditional childhood diseases are also making their presence felt, in part because of neglected vaccinations. The U.S. has seen 16 measles outbreaks this year—89% of cases are in unvaccinated people—and a whooping cough epidemic is the worst since 2012.

“So that’s how we’re starting out,” said Peter Hotez, a pediatrician and virologist at the Baylor College of Medicine. “Then you throw into the mix one of the most outspoken and visible anti-vaccine activists at the head of HHS, and that gives me a lot of concern.”

The share prices of drug companies with big vaccine portfolios have plunged since Kennedy’s nomination. Even before Trump’s victory, vaccine exhaustion and skepticism had driven down demand for newer vaccines like GSK’s RSV and shingles shots.

Kennedy has ample options to slow or stop new vaccine releases or to slow sales of existing vaccines—for example, by requiring additional post-market studies or by highlighting questionable studies that suggest safety risks.

Kennedy, who has embraced conspiracy theories such as that HIV does not cause AIDS and that pesticides cause gender dysphoria, told NPR there are “huge deficits” in vaccine safety research. “We’re going to make sure those scientific studies are done and that people can make informed choices,” he said.

Kennedy’s nomination “bodes ill for the development of new vaccines and the use of currently available vaccines,” said Stanley Plotkin, a vaccine industry consultant and inventor of the rubella vaccine in the 1960s. “Vaccine development requires millions of dollars. Unless there is a prospect of profit, commercial companies are not going to do it.”

Vaccine advocates, with less money on hand than the better-funded anti-vaccine advocates, see an uphill battle to defend vaccination in courts, legislatures, and the public square. People are rarely inclined to celebrate the absence of a conquered illness, making vaccines a hard sell even when they are working well.

While many wealthy people, including potion and supplement peddlers, have funded the anti-vaccine movement, “there hasn’t been an appetite from science-friendly people to give that kind of money to our side,” said Karen Ernst, director of Voices for Vaccines.

“RFK Jr. was a punch line for a lot of people, but he’s serious as hell,” Ernst said. “He has a lot of power, money, and a vast network of anti-vaccine parents who’ll show up at a moment’s notice.” That’s not been the case with groups like hers, Ernst said.

On Oct. 22, when an Idaho health board voted to stop providing COVID vaccines in six counties, there were no vaccine advocates at the meeting. “We didn’t even know it was on the agenda,” Ernst said. “Mobilization on our side is always lagging. But I’m not giving up.”

The kaleidoscopic change has been jarring for Walter Orenstein, who persuaded states to tighten school mandates to fight measles outbreaks as head of the CDC’s immunization division from 1988 to 2004.

“People don’t understand the concept of community protection, and if they do they don’t seem to care,” said Orenstein, who saw some of the last cases of smallpox as a CDC epidemiologist in India in the 1970s, and frequently cared for children with meningitis caused by H. influenzae type B bacteria, a disease that has mostly disappeared because of a vaccine introduced in 1987.

“I was so naive,” he said. “I thought that COVID would solidify acceptance of vaccines, but it was the opposite.”

Lawmakers opposed to vaccines could introduce legislation to remove school-entry requirements in nearly every state, Saunders said. One bill to do this has been introduced in Texas, where what’s known as the vaccine choice movement has been growing since 2015 and took off during the pandemic, fusing with parents’ rights and anti-government groups opposed to measures like mandatory shots and masking.

“The genie is out of the bottle, and you can’t put it back in,” said Rekha Lakshmanan, chief strategy officer at the Immunization Partnership in Texas. “It’s become this multiheaded thing that we’re having to reckon with.”

In the last full school year, more than 100,000 Texas public school students were exempted from one or more vaccinations, she said, and many of the 600,000 homeschooled Texas kids are also thought to be unvaccinated.

In Louisiana, the state surgeon general distributed a form letter to hospitals exempting medical professionals from flu vaccination, claiming the vaccine is unlikely to work and has “real and well established” risks. Research on flu vaccination refutes both claims.

The biggest threat to existing vaccination policies could be plans by the Trump administration to remove civil service protections for federal workers. That jeopardizes workers at federal health agencies whose day-to-day jobs are to prepare for and fight diseases and epidemics. “If you overturn the administrative state, the impact on public health will be long-term and serious,” said Dorit Reiss, a professor at the University of California’s Hastings College of Law.

Billionaire Elon Musk, who has the ear of the incoming president, imagines cost-cutting plans that are also seen as a threat.

“If you damage the core functions of the FDA, it’s like killing the goose that laid the golden egg, both for our health and for the economy,” said Jesse Goodman, the director of the Center on Medical Product Access, Safety and Stewardship at Georgetown University and a former chief science officer at the FDA.

“It would be the exact opposite of what Kennedy is saying he wants, which is safe medical products. If we don’t have independent skilled scientists and clinicians at the agency, there’s an increased risk Americans will have unsafe foods and medicine.”

Outbreaks of vaccine-preventable illness could be alarming, but would they be enough to boost vaccination again? Ernst of Voices for Vaccines isn’t sure.

“We’re already having outbreaks. It would take years before enough children died before people said, ‘I guess measles is a bad thing,'” she said. “One kid won’t be enough. The story they’ll tell is, ‘There was something wrong with that kid. It can’t happen to my kid.'”

2024 KFF Health News. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Citation:

How measles, whooping cough, and worse could roar back (2024, December 9)

retrieved 9 December 2024

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-12-measles-whooping-worse-roar.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.