Three former UK foreign secretaries have today called for the release of Aung San Suu Kyi, currently imprisoned by a brutal military dictatorship in Myanmar.

William Hague, Sir Malcolm Rifkind and Jack Straw warned the ousted leader was jailed on trumped-up charges and said she deserves the chance to lead her country democratically. Ms Suu Kyi is believed to have spent long periods in solitary confinement since her arrest in February 2021. She faces 27 years in prison.

The 79-year-old Nobel Peace Prize winner has become a deeply divisive and controversial figure after refusing to speak out on her country’s extreme violence against its Rohingya Muslim minority.

Her fall from grace is explored in an Independent TV documentary published today, entitled Cancelled: The rise and fall of Aung San Suu Kyi, which takes an unbiased look at her life and the plight of Myanmar.

Lord Hague, who welcomed Ms Suu Kyi to London in 2012 when he was foreign secretary, said it was possible to be critical of the country’s former leader, “but also say we should be campaigning for her release”.

Featuring in the documentary, he said: “She is a political prisoner on trumped-up charges, imprisoned by a military regime in what seems very harsh circumstances.

“And we might disagree with things that she has said and done, but she has been the strongest force for democracy in Myanmar in a generation, and she is imprisoned because she was that force for democracy.”

In 2019, Ms Suu Kyi became a global pariah in the eyes of the international community and human rights organisations after she appeared at the International Court of Justice in the Hague to defend her country’s use of force against the Rohingya.

Lord Hague added: “I think it’s possible to be critical of her, but also say we should be campaigning for her release. She is not a non-person.

“We might suspend judgement on our view of her in history but nevertheless, this is a person utterly unjustly treated by a military dictatorship. And so we should not forget her.”

Sir Malcolm, who was foreign secretary between 1995 and 1997, said her release was crucial to the future of her country, and told The Independent that a popular uprising in Myanmar was reducing the military’s grip.

He said: “Myanmar is being gradually liberated from the armed junta through popular revolt throughout the country.

“Aung San Suu Kyi’s release is essential so that she can provide the political leadership that will be needed when the transition from the army to democracy begins.”

Labour grandee Mr Straw, who was a foreign secretary under Tony Blair, told The Independent: “I share William Hague’s view – she should be released.”

After being freely elected in 2015, Ms Suu Kyi has been held in prison since the military seized power in a coup in February 2021, a move that plunged the country into conflict.

A year later, she was convicted of offences ranging from treason and corruption to violations of telecommunications law, charges she denies. As a result, she faces being kept in detention for the rest of her life.

Although details of her imprisonment have been conflicting, it is thought she has been kept in a cell in a prison in Naypyidaw, north of Yangon.

Australian Sean Turnell, who worked as Ms Suu Kyi’s economic advisor and was sentenced at the same time, described his cell as “completely open to rats and spiders, centipedes and these awful black tarantulas… They’re really little more than animal pens.”

He said political prisoners are held in their cells throughout the day, with just two periods in which they are allowed to leave.

In April a spokesperson for the military junta claimed that Ms Suu Kyi had been placed under house arrest, though no details were given.

Her younger son, Kim Aris, said that no one outside of military personnel has seen her for a long time, and that a number of underlying health issues have been only treated by military doctors.

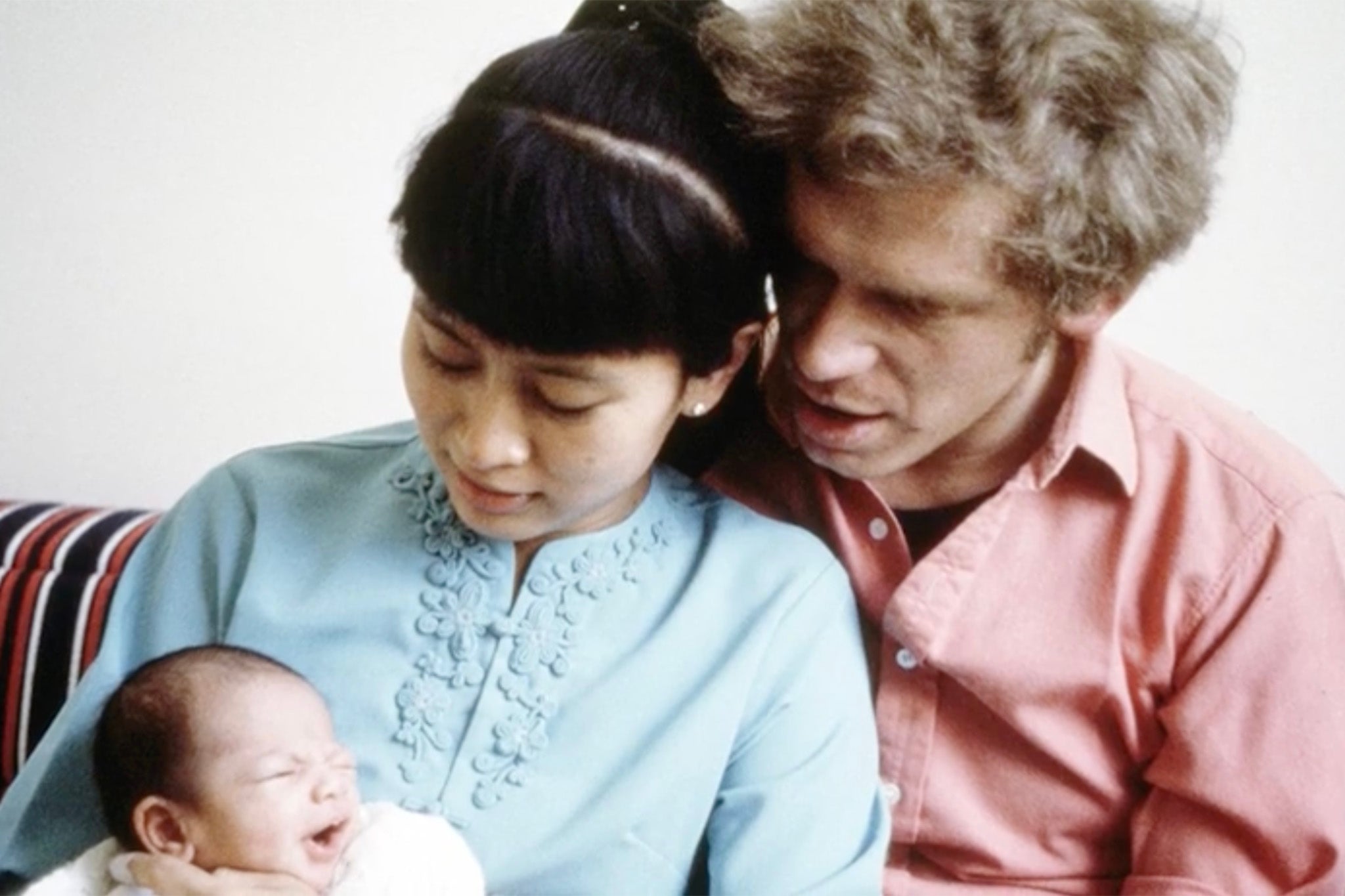

Ms Suu Kyi, who studied at Oxford, married British academic Michael Aris and raised her boys Alexander and Kim in the UK before going back to Myanmar in 1988.

She spent nearly 15 of the 21 years between 1989 to 2010 under house arrest, and her fight for democracy became famous around the world.

Following elections in 2015, the military junta allowed Ms Suu Kyi to become the de facto head of government but only if they controlled the key ministries of home affairs and defence and border control, alongside the military budget.

Two years later, in 2017, the junta cracked down on dissent in Rakhine State among the Muslim Rohingya community. Ms Suu Kyi’s appearance at the Hague two years later lost her international support.

Myanmar’s people have since suffered appalling human rights abuses under military rule.