The embryos of many fish species have some control over when they hatch, effectively choosing their own birthdays.

A study by researchers from Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel now reveals the chemical and biological processes enabling this to happen, showing how individual embryos time their emergence with optimal environmental factors.

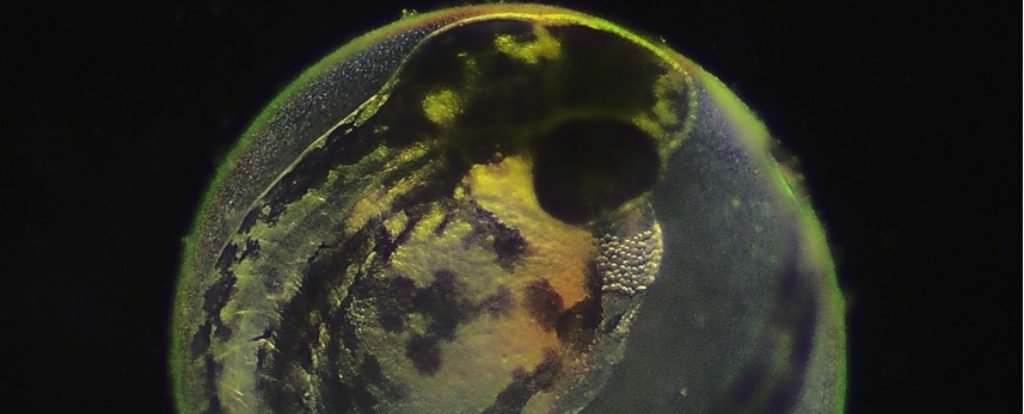

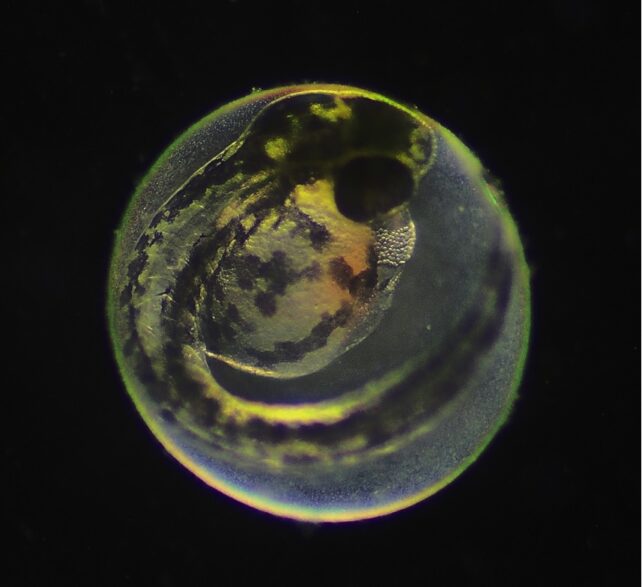

The scientists studied zebrafish (Danio rerio) eggs, finding that the release of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (Trh) from the embryo was crucial in producing enzymes to dissolve the egg wall.

“Hatching is a critical event in the life history of oviparous species,” the researchers write in their published paper.

“The decision to hatch is often carefully timed to coincide with favorable conditions that will improve survival through early life stages.”

Fish species use many different hatching strategies and triggers: zebrafish, for example, usually wait for daylight. Clownfish and halibut wait for darkness. California grunion wait to be washed out to sea.

The research presents evidence of the mechanisms at work behind this delay. In zebrafish, TRH is delivered to the hatching gland via the bloodstream, on the instruction of a neural circuit that’s formed just before hatching and disappears just after.

And it’s not just zebrafish: the researchers also studied the medaka (Oryzias latipes), a distantly related species.

The evolutionary pathways of medaka and zebrafish separated some 200 million years ago, but the same Trh-triggered hatching process was identified in the two species’, in spite of their differences in hatching glands, enzyme types, and embryonic periods.

“Using immunostaining, we observed that like zebrafish, medaka embryos form a transient Trh circuit shortly before hatching that disappears in post-hatching

larvae,” write the researchers.

In humans and other mammals, Trh helps control key biological processes, including heart rate and metabolic rate. It’s notable that the same neurohormone is also used in a different way in fish, perhaps another pointer to diverging evolutionary paths.

The researchers are now keen to investigate details of the hatching process in zebrafish, as well as the similarities and differences there might be in other aquatic species with different approaches to hatching.

Climate change is another consideration for future research: as the world gets warmer, if we’re going to be able to preserve species for generations to come, we need to understand how higher temperatures might influence hatching decision-making that has evolved over hundreds of millions of years.

“It would be interesting to test how conserved the role of Trh is in this process and study variation in the structure and function of the hatching circuitry between species with different hatching strategies,” write the researchers.

The research has been published in Science.