- Juliet Dobson, managing editor

- The BMJ

- jdobson{at}bmj.com

It’s been a tough start to the year for the NHS. This month, 24 NHS trusts in England declared a critical incident owing to overwhelming demand in emergency departments. Pressures were exacerbated by a “quad-demic” of winter viruses, particularly rising rates of flu (doi:10.1136/bmj.r99 doi:10.1136/bmj.r77).12

A report by the Royal College of Nursing showed the extent of the crisis.1 More than 400 pages of testimony by 5408 nursing staff describe how corridor care—treating patients in temporary escalation spaces—isn’t just a problem confined to winter but is becoming normal all year round. The survey detailed the system’s lack of capacity to cope when seasonal viruses hit.

It’s not possible to provide high quality, safe care in a corridor, but is it better than no care at all? Julian Sheather and Matt Phillips say that it may be preferable to nothing (doi:10.1136/bmj.r91),3 but this dearth of dignity, humanity, and respect towards patients “is what is expected in a humanitarian emergency, not a G7 country.” They warn that a guide to the ethics of corridor care, published by NHS England, is a “protocol issued from a system in serious trouble.”

The situation is hugely detrimental to staff who are burnt out, experiencing moral injury, and struggling to work in a poorly managed system (doi:10.1136/bmj.q2858).4 Luke Craddock, a foundation doctor, likens it to a “dystopian system” where patients and doctors empathise with one another, each aware of the difficult conditions they find themselves in (doi:10.1136/bmj.r95).5

What are the solutions? Improved community and social care, with better access to primary care, would reduce some of the pressure. Instead, the government response seems to be further delay to action on social care and an increasing reliance on private providers to deliver elective care (doi:10.1136/bmj.r63 doi:10.1136/bmj.r30).67 John Launer, a GP, laments that plans for reforming elective care are far removed from the reality of general practice and what we know to be efficient and cost effective (doi:10.1136/bmj.r72).8

Any improvements will rely heavily on recruiting and retaining more staff. Scarlett McNally, a surgeon, has concerns that proposed surgical hubs will divert staff and funding from elsewhere (doi:10.1136/bmj.r85).9 Poor workforce planning has created a situation without enough jobs for those graduating or applying for specialty training (doi:10.1136/bmj.r33 doi:10.1136/bmj.r110).1011

Maternity care and staffing in prisons is another area needing urgent attention (doi:10.1136/bmj-2024-080445).12 Pregnant women in prison are at high risk, and the UK is failing to provide them with good maternity care. Spain, Mexico, Italy, and Brazil demonstrate how provision can be improved—for example, by prohibiting or limiting prison sentences for pregnant women and focusing on community based alternatives.

The importance of promoting a patient centred approach was championed by the late John Day, a “pioneer” in diabetes care (doi:10.1136/bmj.q2327).13 At a time when it was considered quite novel, he realised that “empowered patients could radically improve their own outcomes.”

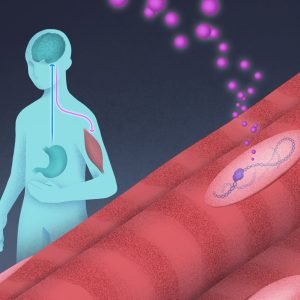

When type 2 diabetes outcomes haven’t improved, can pharmacotherapy offer an alternative approach? Research by Liu and colleagues finds that using SGLT-2 inhibitor dapagliflozin, as well as moderate calorie reduction, achieves higher rates of type 2 diabetes remission and is more manageable than a stricter calorie restricted diet alone (doi:10.1136/bmj-2024-081820).14

What the future holds after an eventful week of geopolitics remains to be seen, particularly in Gaza, where—for now—a fragile ceasefire offers a glimmer of hope. There’s still time to donate to The BMJ’s annual appeal, this year in support of the International Rescue Committee, which is doing valuable work to support children and families around the world (doi:10.1136/bmj.r39).15 Please donate.