At the center of almost every large galaxy in the universe sits a supermassive black hole — and any surrounding clouds of gas, dust, or even stars that wander too close are consumed as they cross over the event horizons of these cosmic monsters.

When supermassive black holes gorge on large volumes of energy and matter in this way, they become capable of creating massive jets of plasma that are shot out through space at close to the speed of light. For instance, one such galaxy, Messier 87, which is roughly 54 million light-years from Earth, is home to a 6.5-billion-solar-mass supermassive black hole which produces 3,000 light-year-long jets of plasma.

And new research, based on observations made by the Hubble Space Telescope, has found that double-star systems sitting close to these jets are living pretty risky lives.

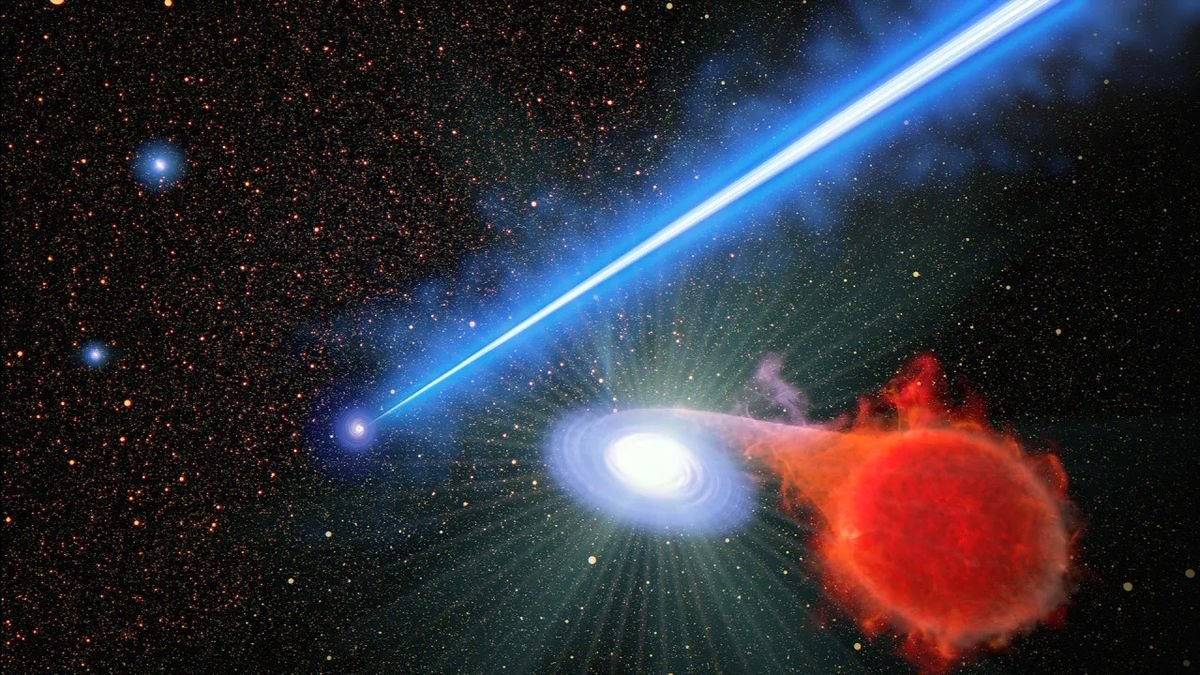

Stars can often find themselves gravitationally bound to one another, forming double-star systems. And sometimes, an aging, swelled-up normal star can find itself with a white dwarf companion — the dead embers of a once active star. In such scenarios, the enlarged star can shed its materials, mainly hydrogen, which are gravitationally drawn to the dense white dwarf.

Related: ‘Missing link’ black hole lurks in strange binary system with red giant star

However, as hydrogen accumulates on the surface of the white dwarf, the star can reach a critical tipping point. After that point, the process spurs an explosion. You can think of it like a hydrogen bomb. Such explosions are called nova, and they are relatively common throughout the universe. In fact, one is expected to happen quite soon with a star called T Coronae Borealis — and, in a rare turn of events, scientists think that explosion will be bright enough to make a “new star” show up in our night sky.

Intriguingly, astronomers found that nova eruptions are almost twice as likely to occur in double-star systems located in the vicinity of Messier 87’s supermassive black hole plasma jets. Initially, astronomers thought something about the jets might be enhancing the fueling process and therefore the rate of explosions, or even birthing new double-star systems in its vicinity.

But Alec Lessing, an astronomer from Stanford University, and lead author of the paper reporting on these findings, isn’t quite convinced.

“We don’t know what’s going on, but it’s just a very exciting finding,” Lessing said in a statement. “This means there’s something missing from our understanding of how black hole jets interact with their surroundings.”

Not long after Hubble was launched in 1990, astronomers pointed the telescope towards the center of Messier 87, where the galaxy’s supermassive black hole dwells. At the time, they observed strange blue “transient events” near the black hole, but the narrow field of Hubble’s camera at the time meant the scientists couldn’t compare how often these events were occurring in that location when compared to the rest of the galaxy.

“We’re not the first people who’ve said that it looks like there’s more activity going on around the M87 jet,” said co-author Michael Shara from the American Museum of Natural History in a press release. “But Hubble has shown this enhanced activity with far more examples and statistical significance than we ever had before.”

The evidence for the jet’s influence on the surrounding stars was collected over a nine-month period, with Hubble observing with its newer, wider-view camera every five days. Despite nova eruptions being common events in galaxies as a whole, the new research further illustrates the influence that supermassive black holes can have on activity and evolution of galaxies.

The research was published on Sept. 27 in The Astrophysical Journal.